Why parents aren’t reading to kids, and what it means for young students

Lifestyle

Audio By Carbonatix

7:00 AM on Friday, January 9

By Jessika Harkay for The 74, Stacker

Why parents aren’t reading to kids, and what it means for young students

Jeana Wallace never enjoyed reading as a child.

The books she read in school didn’t interest her and “constant deadlines made it even harder to connect with the stories,” she said. Reading was a chore, something to rush through for a test or school assignment.

So when Wallace became a mother in 2019, she didn’t read to her son at home often — about once or twice a week, “maybe not even that,” said Wallace, who lives with her family in Frankfort, Kentucky.

That changed around the time her son was three and she was working at a local adult education center where she helped develop a family literacy program. There, she learned about research on how reading to young children daily can improve school readiness, develop language and listening skills and promote social-emotional growth.

Now her family reads “three or four books every single night,” she said.

The payoff has been clear: Her son, Levi, has an impressive vocabulary for a soon-to-be six-year-old, can speak in complete sentences and most importantly “his confidence is boosting tremendously.”

“His life is going to be so much easier because he loves to read,” Wallace said. “I didn’t want him to grow up hating to read [like I did]. … I always struggled with comprehension and remembering what I read, and so it’s challenging when you don’t love doing it.”

Wallace’s initial resistance toward reading may be the new norm among parents, The 74 reports. Earlier this year, HarperCollins UK released a report showing a steep decline in the number of caregivers who read to their young children.

For many new parents, a dislike of reading stems from their own classroom experiences in the early 2000s that emphasized reading as a skill for testing. Many are also unfamiliar with the importance of reading to young children or may instead undervalue reading because of a dependence on online educational programs that have limited benefits for learning.

For children not getting the benefits of being read to at home, the opportunity gap has widened, with those young students entering school unprepared compared to those who have been read to.

“The gap really begins very, very early on. I think we underestimate how large a gap we’re already seeing in kindergarten,” said Susan Neuman, professor of childhood and literacy education at New York University, adding she recently visited a New York City kindergarten classroom and saw some children who only knew two letters compared to others who were prepared to read phrases.

A 2019 Ohio State University study found that a five-year-old child who is read to daily would be exposed to nearly 300,000 more words than one who isn’t read to regularly.

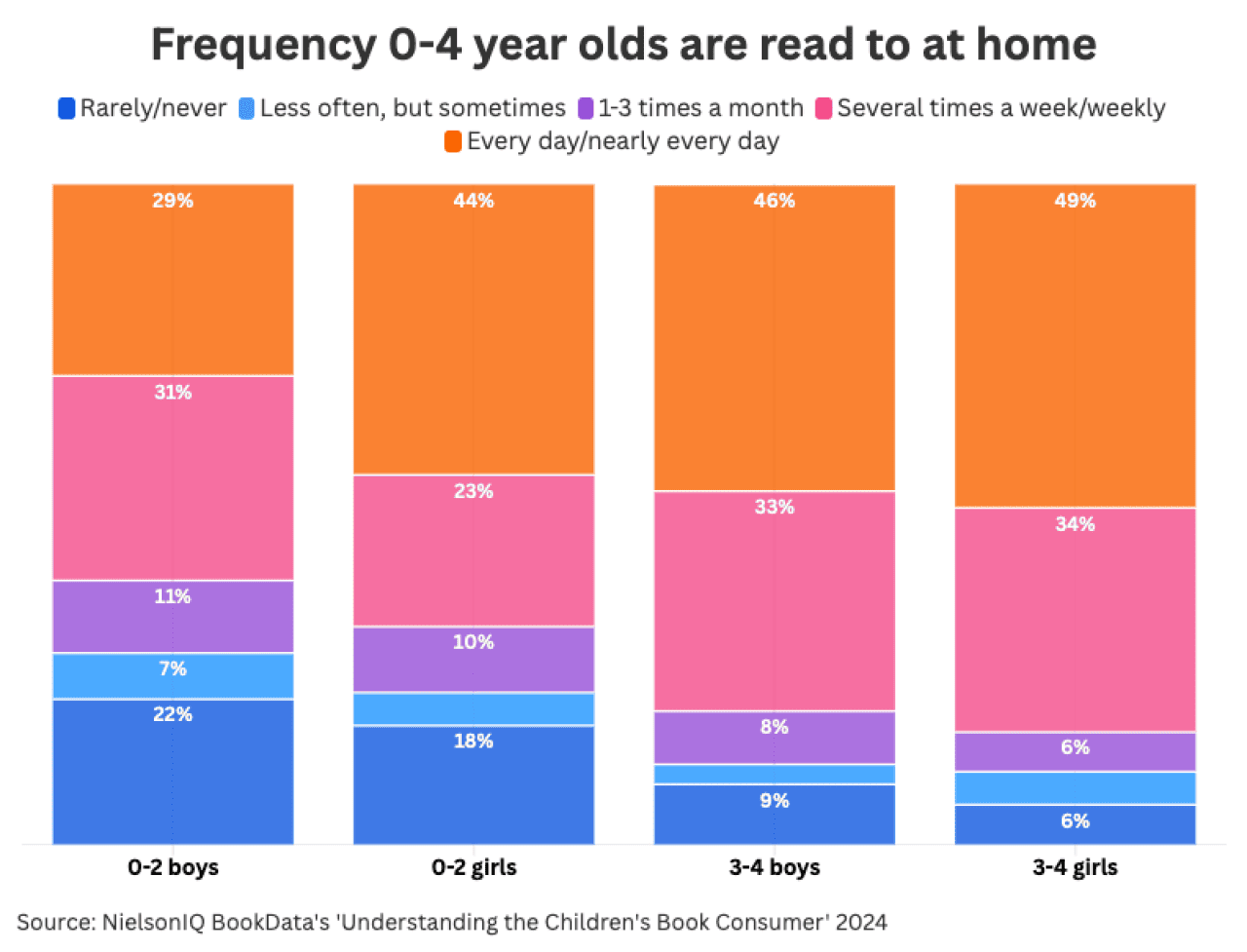

The 2025 HarperCollins survey found that less than half, around 41%, of children between the ages of zero to four were read to every day or nearly every day; a decline of nine percentage points from 2019 and 15 percentage points in 2012.

The survey found that about a third of parents read to their babies and toddlers weekly. Around 20% of parents said they “rarely” or “never” read to their child between the ages of zero and two and 8% of parents said they “rarely” or “never” read to their child between the ages of three and four.

It’s something that doesn’t surprise early literacy experts in the United States, who suspect similar trends across the country, believing the decline in early literacy reading is likely even higher than reported.

“Frankly, parents … will often lie because they know it’s important to read, so they’ll exaggerate the amount of time they’re reading,” Neuman said. “I think the bottom line is reading is declining big time, not just for parents reading to children, but for all segments of our society.”

But, some of the youngest parents, those born between 1997 and 2012 — also known as Gen-Z — are more likely than past generations to view reading as a school or work activity rather than fun or beneficial, according to the HarperCollins survey and early literacy experts.

For many young adults, their experience in the classroom, especially during the peak of the No Child Left Behind Act, which mandated annual standardized testing in the early 2000s, took the pleasure out of reading and instead instilled a shift toward “skill and drill,” practices, said Theresa Bouley, an education professor at Eastern Connecticut State University.

“We went from fourth grade and sixth grade testing to every year — third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth,” Bouley said. “At that time we started using less books, more programs, more skill and drill and the purpose of reading only became learning different aspects of reading, like phonics or things like that, and not actually for purpose or pleasure or even having time to apply the skills they’re learning to actually read.”

An entire population of students may have lost the value of reading, and combined with being the first generation of digital natives, the United States’ youngest adults are among those who are now seeing some of the largest declines in literacy skills.

And it’s likely they’re passing their habits down to their children, which can have crucial repercussions on the youngest emerging students’ social-emotional health, cognitive development and future literacy skills.

“Children are not seeing their caregivers actually reading books and that sends a really strong message. … As a three-year-old boy, [they] want to do what dad’s doing,” Bouley said. “I think it’s equally important … [for a] child’s understanding of the purpose and joy of reading to see their parent reading.”

In Wallace’s case, she was able to make up for some lost time.

For other families, however, there isn’t a lot of opportunity to close the gap once a child enters school.

“There’s an assumption nowadays that when kids get to kindergarten, they need to know their letters and their numbers and this is highly predictive of whether or not they’ll be successful at the end of kindergarten and at the end of third grade,” Neuman said. “Teachers have a very short time to work on these kinds of things, and when children are that far behind, … I don’t see realistically that a teacher will be able to give the intensive support that children will need in order to catch up.”

Why does reading to our youngest children matter?

Early literacy researchers believe there’s a common misconception that reading to a child when they’re babies or young toddlers is useless because the child doesn’t understand what’s going on.

The activity, however, “is a lot more than just reading and reading books,” Bouley said.

Reading aloud creates a foundation for literacy, she said.

Studies have shown it helps children develop communication and fine motor skills and also promotes oral language skills, which are a strong predictor of future success in school.

Books also open up a world of vocabulary that isn’t used in day-to-day language when parents speak to their children, Rebecca Parlakian, senior programs director at Zero to Three, an early childhood nonprofit, said.

“Shared reading does predict child vocabulary prior to school entry, and vocabulary predicts later emerging literacy skills. We also find that the quantity or frequency of parent-child book reading predicted children’s receptive vocabulary, which is the words they understand, their reading comprehension skills and their desire to read,” said Parlakian.

A study released in August found that reading aloud to a child at eight months old was linked to language skills at 12 and 16 months, “so even infants being exposed to ongoing rich language made a difference,” Parlakian added.

And while “language and vocabulary are the primary benefits,” books also support “social-emotional skills because children are being exposed to the feelings and motivations of characters other than themselves,” Parlakian said.

‘Skill and drill’

Reading aloud is also beneficial for children to develop a positive association with the activity.

“There’s a lot of warm fuzziness and social emotional development that goes on. So now in kindergarten, if the teacher whips out a book, I remember my dad read me that book,” Bouley said.

Having a positive association with books, without the pressure of assessments or skill tests, allows young children to understand the value and fun of reading.

“It builds connections,” said Carol Anne St. George, a literacy professor at the University of Rochester. “People talk about text to text, text to world … and those are the kinds of things that help children cognitively think and classify their world around them.”

But, it’s becoming a lost art.

Instead, reading in schools has become performance-based activity or test preparation.

“Whether it’s parents at home and also teachers in schools, we’re seeing so few books, and so few opportunities for children to read — really read,” Bouley said.

There’s a pressure in the United States to “press reading very, very early,” Neuman added.

“If we look globally at other cultures where children are more successful, like Finland, … they don’t start formally reading with children with the expectation they should read by third grade. They recognize that play is really important in these early years, that talk and oral language is extremely important, and they focus on other things,” Neuman said. “But, we’re in a race.”

That “race” has contributed to changes in curriculum and a pullback on activities like read-alouds in the classroom, which Bouley, Neuman and St. George said they’ve all seen.

“I don’t see that time really devoted and yet that’s so critical,” Neuman said. “The language that they’re getting through that storybook and experience is really imperative. I don’t see it as much. I see a lot of skill and drill.”

Among some researchers, there’s a belief that the shift happened around 2002 as the United States shifted toward an annual testing model.

“We became inundated with assessments and preparation,” Bouley said. “So first graders, second graders, they’re constantly getting these assessments that definitely take the purpose away from reading for enjoyment to reading as skill.”

Timed reading fluency assessments, for example, “just shows kids that you can’t go back and read accurately,” and “all that matters is how many words you can read in one minute,” Bouley added.

“So children get these messages about all that matters with reading and none of it has to do with comprehending a book and enjoying a book,” Bouley said. “It got much worse, or even started after No Child Left Behind, and then it’s just become worse and worse.”

Many of those former students are now parents, like Wallace, who may struggle with passing on literacy skills because of their own experiences in the classroom.

From one technology-raised generation to the next

Reading for pleasure in the United States has declined by more than 40% between 2003 and 2023, according to a 2025 study from the University of Florida and University College London.

The same study said it’s unclear whether levels of reading with children has changed over time, but it did find only 2% of its participants read with children “on the average day,” despite 21% of the study’s sample having a child under nine years old.

Declining literacy levels also go hand-in-hand with the rise of the internet and accessibility to portable devices.

“This is a generation where we really begin to see a drop in reading for pleasure because they were part of that initial wave and flood of digital media that was totally unregulated. We had no research on the impact,” said Parlakian.

Those patterns from the first generation of digital natives are now being mirrored to another generation of children.

A study released earlier this year from the PNC Foundation reported that about 35% of parents said some of the biggest challenges in reading to children are that the child prefers screen time or won’t sit still long enough.

“When we introduce screen time very young, and we don’t manage the amount of time children are spending on screens, … it can be difficult for children to transition from such an exciting medium to a medium like a book that may initially feel not as exciting,” Parlakian said.

While some parents may argue their young children may not have to read as much with physical books because they’re instead benefiting from educational programs on tablets or phones, early literacy experts said there’s a difference between the two activities, both social-emotionally and academically.

A lack of reading time with a parent possibly means losing bonding time. With a tablet, a parent can hand it off and walk away, Bouley said, but when it comes to reading a book, it demands a parent’s full presence.

Skills-wise, until around the ages of five and six, children have a “really hard time and are incredibly inefficient at transferring learning that happens on a screen to real life,” and vice versa, Parlakian said.

Reading also requires stamina — and educational programs on tablets or other devices, instead offer instant gratification, Neuman added.

“A good storybook often takes a bit of time to develop. … There’s literary language that children are learning, … and games are very colloquial, they’re very short-term and they’re bits of information that don’t connect,” she said. “Children aren’t developing comprehension, … even when they begin to learn the print, what we’re seeing is they don’t know the meaning of the print, and that’s a big problem.”

Adopting early reading practices for the Wallace family means comprehension hasn’t been a problem for five-year-old Levi, who points out the words he knows in his children’s Bible, or in his other favorites like “Little Blue Truck” or “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?”

“He can read almost a whole page by himself. He gets really excited and he has to go around and show his dad or we’ve got to FaceTime and show his mamaw,” Wallace said. “He wants everybody to see he knows how to read.”

This story was produced by The 74 and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.